Little Legal Things

I never thought I’d say this, but thank god for lawyers.

I had assumed my business was so lil and cute that I wouldn’t generally need legal advice. Until the day I did! (Isn’t this always how the story goes?) My lawyer taught me so much about the little legal things I didn’t know I 100% needed.

So now I’ll tell you.

But if you’re like me, you also want the tea on the legal sitch I was in. I’ll start there.

Someone we’ll call Jon signed up for my Data Viz Academy. After a few weeks, he wrote me to say he’d downloaded all the templates, got what he needed, and would now like a refund.

After I stopped 🤣, I replied with the statement I have posted in multiples on the website, including on the payment page: There are no refunds.

Jon f-r-e-a-k-e-d. He started emailing me many times every day.

He claimed I was taking away his vacation with his daughter.

I was causing him so much stress he couldn’t function at work and will lose his job.

He was going to report me to the Royal Bank.

He’s really very sorry about his rash responses and now that he’s calm could he please have a refund?

He has no choice but to blast me on social media.

My work is all trash and why would he want it anyway.

Not much rattles me anymore. I assumed he has some mental health struggles and that this would die down soon. But the day I got 10 emails in a 5 hour span of time I decided this was harassment and contacted a lawyer.

She helped me tighten my legal bolts.

I had been missing a few elements. There’s nothing I could have done to keep someone like Jon from being very Jon up in my inbox but I had some holes to close. Some of these legal lessons are only relevant to online courses but others likely apply to you if you have a website.

Document everything.

First order of business was to compile the timeline of actions and communications from Jon.

In my searching, I discovered that Jon had actually already done this to me years earlier, back when I did allow refunds. Same thing – signed up, downloaded a bunch of my resources, then asked for a refund. Ya busted, Buddy.

This information all went into the cease and desist letter to Jon from my lawyer.

Beef up the terms and conditions.

The terms and conditions need to include the no refund policy (mine did) with extra language that applies to European regulations. Because Jon lived in Europe. As do many of my students. And Europe has a 14-day refund period for online purchases, no questions asked. UNLESS you have something explicitly addressing it in your T & C.

This could be something to consider if you have any kind of sign up form on your website. Like, if you have a freebie people can download. Your terms and conditions would be where you’d state what people can and can’t do with your intellectual property if they download it. Would you be ok if they posted it on their website? If they printed 800 copies and distributed them at a conference without your knowledge?

We both know that no one reads the terms and conditions. But this is how you protect yourself if something comes up. And it probably won’t. Until it does.

Make agreement to the T & C a mandatory part of sign up.

To be extra legal, you can’t just say “By clicking the Submit button, you agree to the terms and conditions.” Nope. You gotta make people manually check the box – active consent – that says “By checking this box you agree blah blah blah.”

You’ve done this yourself on countless websites and it’s annoying but now you know why.

The annoying cookies notice.

Again, if you collect people’s information at all, your website / customer management system is using cookies and you’ve gotta tell people. It’s the worst, isn’t it? I tried to make mine at least slightly on brand.

This has nothing to do with The Jon Problem but my lawyers were like, while you’re in the site making changes…

Post a privacy policy.

You have to also tell people what you’ll do to protect their name and email. If you’re going to share their email whatsoever, you have to tell them. That includes sharing it from your website to your email newsletter program, for example. If you accept payments online, you have to spell out how credit card info is kept private.

Thankfully, a lot of this language is prewritten boilerplate and you can buy templates from my lawyer here. (I don’t get a kickback or anything, I just want you to feel some relief that you don’t have to invent this from scratch.)

Keep in mind that I’m not a lawyer. I’m just telling you stories about the legal lessons that I learned and you know I’m legally required to tell you to get your own lawyer.

I hope you never have your own Jon Problem. But chances are, the more you grow your business, the more you’ll attract a personal Jon. Please please learn from my experience and put some protections in place.

When the Client Overruns the Schedule

Are we all in on the farce?

When you’re proposing a project and the prospective client wants deliverables attached to deadlines, does everyone know it’s pretty much bullshit?

I’m picking dates out of the clear blue sky. They’re as fictional as what the Jetsons thought the future looked like.

Because 95% of projects do not go according to plan. How could they? There are just so many unknowns.

Well, to be honest, the one thing I do know for sure is that the client will not get me feedback on the draft deliverables in a timely manner. It doesn’t matter who they are or how much I like them or how good the intentions are or how much we all want the project to succeed.

It just doesn’t happen.

I shouldn’t be so hyperbolic. I do get timely feedback once in a while – and it invariably comes with requests to undo things they previously asked me to do.

Either way, we will not meet the deadline.

Early Founder Stephanie was such a people pleaser that I’d let clients trample my boundaries and timelines and mental health. Old Me would have pulled some late nights and early mornings turning these large requests into miracles before the deadline.

Which we all knew was arbitrary in the first place.

How can we handle a schedule overrun while also maintaining our sanity?

When this happened last year, my team and I could see a schedule overrun early on.

Red Flag: If your project involves data collection. Even if that’s just a matter of scraping existing data from online sources. You will overrun the schedule.

Communicate early. I began telling the client “I need x by y date in order to stay on track for this project.”

Communicate often. Though they said they understood, they also blew past the dates I had put in place. Every single time. I changed my messaging to “We’ll do our best to get as far as possible in the time we have but I’m giving you a heads up right now that it’s likely we won’t make the deadline we stated in the contract.” I said a version of that so many times that it came as no surprise when the deadline was in the rearview mirror.

Then a wrecking ball hit our timeline: My point-of-contact took a new job. We switched horses mid-stream. New horse asked for us to undo things the last horse asked us to do. This set us back a month. My first two strategies to prevent an overrun were moot.

Communicate clearly. This is the point where my team and I could see that deadline was gonna crash into deadline and the whole project would spill over past the contract’s end date.

Option A was to stress out my team with demands to push harder and just make it happen. But who wants to live that life??

Option B was to work with the client to extend the end date on the contract and overlap the end of this project with the start of new projects we had on the horizon. In some cases, my team had, months earlier when the sky was bluer, told other clients they couldn’t begin work until another project (this one) ended and had promised start dates that were now looming. Extending this end date would still create a stressful scramble.

Ok there may be 23 more options but I chose Option C, which was “It’s no one’s fault in particular but we are unfortunately so far behind the schedule at this point that we won’t make our contract’s end date. My team and I have obligated time in our schedules through the end of the original contract period and we won’t be available after that date. We can work together to hand off the project to you to wrap up. If you still need our input, we can consult on an hourly basis starting in October.”

I mustered up my courage, did 10 jumping jacks, and hit send on that message.

They understood. They appreciated the plan for a hand-off. And they asked for an hourly contract to start in October.

Or, at least, that’s what the email said. For all I know, they were cursing my name back at their office. And it was that reaction I was actually afraid of. I didn’t want to make my clients mad at me.

Remnants of that old People Pleasing Stephanie were still kicking around.

The rational part of me knew that the clients were the ones who ignored the timeline. This wasn’t on me or my team. Yet that logic couldn’t quiet the fear of someone being mad at me. You can’t logic an emotion.

You know what worked?

When I realized that the choice was between taking the risk that my clients would be at me and being absolutely sure I would be mad at myself for allowing a stressful work culture that required multiple all nighters to make up for other people’s errors.

I’m still people pleasing. I’m just counting me and my team as people, too.

Laughable Contract Clauses

I have a short and sweet contract. It’s 1 page long. As soon as I sniff that a potential client and I are getting to the contract phase, I offer to draft one up for us. Because I hate – HATE – dealing with boilerplate contracts.

They take a hundred years of my life to read closely.

They’re full of legalese I’m sure is intended to make the average Jane feel dumb.

And they’re usually distributed without regard for the actual scope under negotiation.

Corporate and government legal departments are not writing contracts with the best interest of your small business in mind. They assume you’re so thirsty for work you’re going to sign without reading very closely.

I took one for the team and identified several ridiculous contract clauses that you shouldn’t agree to.

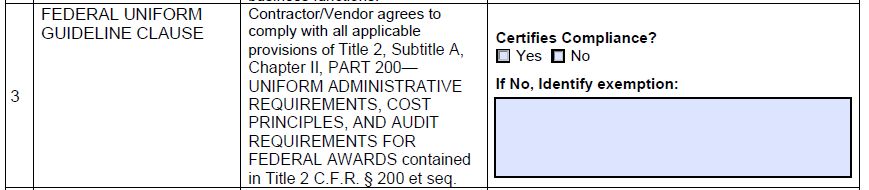

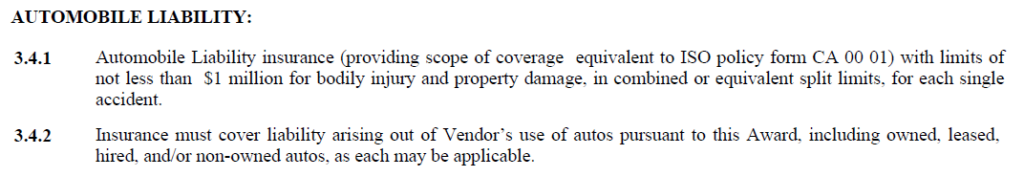

Laughable Contract Clause A:

I’m absolutely not looking up some arcane statute buried deep in some document that isn’t even linked to attest to my compliance.

Among many other statues in one particular contract, I had to swear to uphold one single line that linked to a set of provisions that’s 417 pages long.

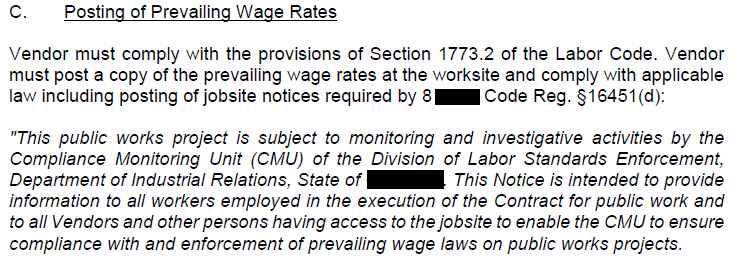

Laughable Contract Clause B:

This is only 25% of the required wording they want me to print onto a flyer and post in my office. Where I work by myself. While many of these clauses don’t apply to solo enterprises, they also aren’t applicable to the modern workforce, where large teams work remote. What, are we gonna print and mail flyers that every employee has to post in their living room? No.

I had a contract that wanted me to attest I’ve done all of this under penalty of perjury.

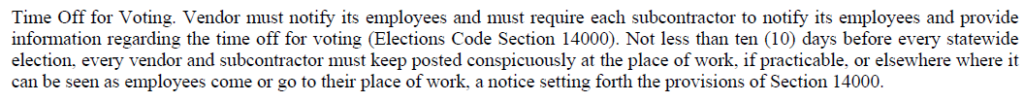

Exhibit C:

Though I’m with you in spirit and will absolutely vote, I’m not. posting. flyers.

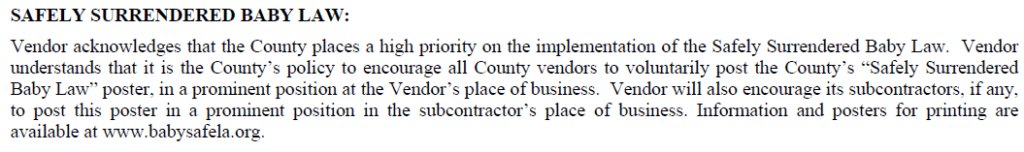

Exhibit D:

Can you even imagine what my office would look like with all these freakin posters?

Here’s a good one. Exhibit E:

I have to provide proof of auto insurance? For a virtual workshop?

I’ve argued with procurement departments over this one, multiple times. Cars are not involved in the execution of this work. What if people don’t even own a car?

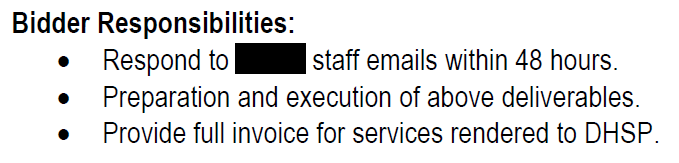

Exhibit F:

Not even 48 business hours. Nope. Not answering emails on a Sunday.

Plus, this contract had three different places where I had to agree to provide a certification of compliance that I don’t use child labor.

I’ve reviewed a contract for a colleague new to the biz where the contract required a physical fitness test. For a virtual design gig.

Have you ever seen a laughable contract clause? Please tell me about it.

The boilerplate is so fully cooked that most procurement officers don’t even look at the scope of the work under contract to see if it’s applicable.

You might be thinking, oh screw it. If procurement isn’t looking at the contract, they surely won’t follow up and ask me for this documentation.

And that would be a very foolish move, my dear.

I have 100% been asked, within 10 minutes of emailing my signature on the contract, for every bit of documentation.

The advice is, of course, to get a lawyer on your team who can review each of your contracts and create counters when necessary.

To be totally honest, I didn’t have the money to hire a lawyer to review each piece of paper when I got started.

I also don’t need a lawyer to recognize ridiculous when I see it.

These days, though I do have a lawyer I can hit up when needed, I make the first move and red line any clauses that don’t work for me. Contracts aren’t set in stone. You have the authority to ask for adjustments or strike outs.

That also means the potential client has the authority to reject your edits and create an impasse. At which point you get to decide if getting a certification of compliance that you don’t hire children is worth the effort. And THIS, my friend, is why you don’t count the money until the ink is dry.

A Halloween Horror Story

On the occasion of Halloween week, let me impart a bit of horror with a story about a mistake I made on my very first venture working for myself.

My maiden voyage was a client who I had also worked with at my full time employer. She was interested in some (cheap) design work that was outside of the scope of services my now previous employer offered.

I was going to design the pages of a textbook.

Why?

This was miles away from the work I knew how to do. On another planet. Not my circus.

But I said yes anyway because, as all new entrepreneurs do, I was desperate to make sure I could pay the bills.

The Terms of the Contract

I wrote up a contract that said I’d get:

20% of the total cost upon delivery of the mockup of a dozen key pages.

50% at the delivery of the full first draft.

30% at the conclusion of the work.

We sign, I break open the champagne.

The Reality of the Contract

The next morning I crack open my laptop and get to work.

Within two weeks I had a dozen pages I was happy with and shipped those over to the client.

She took about a week and then got back to me with:

“Thanks – these look good. We’ve got it from here.”

Me: “I’m so glad you love the layout. I’ll get started on the full draft.”

Her: “Sorry that wasn’t clear. We don’t need you to make the full draft. We’ve found a grad student who will work from the models you set up and create the rest of the book.”

What would you do here?

The Terms of the Contract, Revisited

I scrambled to the contract. Yep, there WAS a cancellation clause! Got you!

Oh wait.

The cancellation clause said that either party could cancel with a 10-day notice and that the contractor (me) would be compensated for the work completed to date. (This is actually very boilerplate – contracts are not designed to protect the contractor.)

Which means, yep, I was stuck with 20% of the compensation I was counting on (all those bills to pay) even though developing that 20% took the vast majority of the intellectual work.

The client was completely within the bounds of the contract, though both the contract and the client’s use of it (I can now see) were ethically questionable.

What would you do here?

I cried. I got mad. I wallowed in the injustice for a day and then I set about finding more work.

And I embroidered this experience into my mentality. Lesson fucking learned.

Ok, friend, here’s what you can do to keep yourself out of this mess in the future.

- Negotiate better cancellation terms. What could it say? I don’t even know. Because you don’t want to get in a rare situation where YOU need to cancel but can’t because you wrote out a clause that’s too restrictive. I’m actually not sure there’s much you can do here, but maybe you’ll think of something creative and contract lawyers can help.

- Reallocate the percentages and due dates. I’d ask for a percent of the contract at signing (pay bills). I’d ask for a much higher percentage due at the mockups. My allocations would look something like this:

- 15% due at signing

- 60% due at mockups

- 15% due at first full draft

- 10% due at final full draft

This way, you get the bulk of the payment when you deliver the bulk of the intellectual property. If your client ever pulls what happened to me and ditches you upon receipt of the mockups, you’re only out 25% (which would still suck, but not as much).

Your pay isn’t connected to your time. It’s connected to your intellectual property.

Want a postlude? It became clear to me that this client honestly hadn’t thought she’d done anything wrong or morally questionable. Because a year later she reached out and asked me to work on another project.

Credit Where It’s Due

Have you seen Native deodorant? It doesn’t have aluminum and the unisex-intended scents are pretty decent.

It became so freakin popular, within two years CEO Moiz Ali scaled Native to $100M, sold to Proctor and Gamble, and got that golden exit that so many startups dream of.

A dramatic two year ascent, between 2018 and 2020. All because Ali got curious about the label on his deodorant one day, as the legend is told on Native’s About Us page:

Only, this is mostly bullshit.

Two years after his golden exit from Proctor and Gamble, Ali finally told us his version of the origin story, over on Twitter (or X).

I’ll link and screenshot here because I can’t believe this link still works – he kept this thread in existence.

Are you seeing this? Dude didn’t invent anything. He repackaged a woman’s product and resold it under a different name and catapulted to billionaire status.

He goes on to detail the benefits of this resell-Etsy strategy.

After a bunch of WTF in the comments, he further insists that she wanted it this way. We never learn her name, she just remains an anonymous woman. We don’t even get a link to her business so we could support her in some way.

She gets no credit on the website.

No golden parachute out of P & G.

This story isn’t new, of course. We have countless stories about scientific breakthroughs that result in a Nobel awarded to the man while the women in the lab get zero recognition.

Though this happens everywhere, it’s a particularly American story to be self-sufficient, self-made, reliant on no one. It’s just also bullshit.

(And how, in a particularly litigious America, do we not at the very least have lawyers questioning whether credit should be shared as a part of their due diligence???)

(Sorry, that question actually has an obvious answer that’s connected to the overall issue here: Patriarchy.)

Ok, this makes my blood boil to the point where I have to intentionally cut off my elaboration of the problem to turn toward solutions or this will become the longest post you’ve ever scrolled.

If you’re the creator

Protect your IP. Soooo many contracts have, as boilerplate, that you as the consultant must assign your intellectual property to your client to use, change, and distribute as they wish with zero credit or compensation to you forever and into infinity. Do not sign. Ask for this clause to be struck or modified.

License your IP. Rather than give up her deodorant recipe (or, since we don’t know the whole story, sell her deodorant recipe for what was surely, in proportion, a very low price), the unnamed inventor could have allowed Native to rebrand her recipe for a limited amount of time, in exchange for a per-stick or percentage dollar amount. The limited time is important here so you have the ability to renegotiate the terms.

Sell your IP for very good compensation. I see so many creators who fall into the mentality of It didn’t take me long to do this, so I can’t charge very much. Time does not equal money.

Value equals money. And if you can produce something valuable in 15 minutes that took other people 3 hours – that’s awesome. It should be expensive, because you figured out processes that no one else knows.

Most startups are broke, so how would this work? Equity. The deodorant creator also could have negotiated equity in exchange for her recipe, which would have put her in the multimillionaire zone after just a couple years.

If you’re the CEO

It’s your ethical responsibility to make your partner is aware of these options. If you’re trying to run a business that aligns with your values. And I think that’s why you’re here.

If it’s too late, like let’s say you’re working from your Grandma Carol’s recipe and she passed away last January, you need to put Grandma Carol all over your website. She should be woven into your company’s origin story. (And if you’re working from someone else’s grandma’s recipe, you owe her descendants compensation and equity.)

Ok you might not be working at such a grand scale, but you can still give credit where it’s due. For example, in past issues of my dataviz newsletter, I included a regular section that showcased everyone behind the scenes here. All the staff that hold workshops for me. My brother who troubleshoots any computer issues. My mom who does all the finance stuff. Even Holly, who cleans my house.

This includes where you got your inspiration and ideas.

I was once asked to review the first chapter of a book, as part of the editor’s process of deciding whether to work with the author to write the whole thing. I was close enough to the subject to recognize that the bulk of the ideas were not original. Nor were they cited.

This author’s ego was so fragile he couldn’t share the spotlight he was trying to turn on himself.

But you know what citations do? They show you know what you’re talking about. Sharing credit makes you stronger.

What’s not bullshit is that it takes a village. So give your village credit and compensate them well.

Who has been keeping your boat afloat? Instead of emailing me this week, I want you to email them.

Ethical Riders

“We met as a group and have decided we’d like the dashboard’s graphs to be red if the metric is trending bad and green if the metric is trending in the right direction.”

Ok, what would you do here?

Because the client is asking for a change that would make the work inaccessible to people who are red-green colorblind.

Just do it because they are paying you?

Push back?

I pushed back. Here’s what I said:

I strongly advise against this. You told me during our initial conversations that a key tenet of your [name-drop-worthy] foundation is equity. Choosing red/green makes you inequitable. Like I recommended in my initial sketches of the dashboard, let’s use orange and blue instead. Need another reason? Your logo is red. So assigning red to the bad data would conflate “bad” with YOU. Don’t do this. You hired me to give you the best possible advice and that’s my advice.

Dear Reader, they pushed back on my push back. They told me to do it anyway.

And that’s when I wish I could’ve quit the project.

Because now we were consigned to create something I would never be able to share. What good is having a name-drop-worthy client if you’re so embarrassed by them that you’d never drop the name?

I was venting about this on a call with my Boost & Bloom students (to show that even seasoned entrepreneurs can have things turn sour) when one of them asked me:

Could you put ethical riders in your contract?

Holy crap.

Yes.

Of course I can.

You can put anything you want in your contract. (Granted your prospective client may retreat from the engagement – but you’d have your dignity intact.)

Until now, I’ve really only thought of ethical riders when it comes to speaking panels.

After I screamed into the internet about manels in data visualization, I wrote up an inclusion rider that stipulates that my role in the conference is contingent on the requirement that other featured speakers and panelists are proportionately representative of United States (or wherever this is taking place) demographics, meaning approximately 50% women, 50% people of color, 20% people with disabilities and 5% LGBTQ. I can cancel at any time with no notice if this stipulation is not met.

Inclusion riders are a way for people with privilege to open up space for those who have been traditionally overlooked.

This notion of an inclusion rider came to my attention through the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative, where they work with actors to include such riders in their contracts, laying out the expectation that, collectively, cast and crew need to be an accurate reflection of society. They even provide a contractual template.

Employment contracts can contain morality clauses that say you can be fired with cause for engaging in acts that damage the company’s image or reputation.

With these specific models already laid out for us, I’m curious what it could look like to apply the same idea more broadly so that I’m not committed to begrudgingly making this inaccessible dashboard.

I’ve got a great attorney who can surely help craft the right language. But she’s going to ask me how we’ll define “ethics” – just in the same way that those morality clauses have to spell out precisely what acts violate company morals, with specific examples. And this can be especially tricky in areas like accessibility, where the possibilities are rapidly expanding.

But let’s not allow the trickiness to keep us from even trying.

The integrity of aligning our work to our values is too important to give up just because it sounds like it’ll be hard.

As is so often the case, we often learn we have boundaries after they’ve been violated. So, given your hindsight, what specific examples would you want to see included in ethical riders for data visualization? Email me with a nomination.

Talk To Your Boss

Ryan (fake name) told me over Zoom that he was thinking about launching his own business, training dogs to walk on their front legs (fake business).

Me: Cool! When are you putting in your two weeks?

Ryan: Oh I wasn’t going to quit the day job. I just want this to be my side hustle until I can grow it more.

Me: Uh, but isn’t your day job also training dogs to walk on their front legs?

Ryan: Yes, but my boss is cool.

<red flags whipping up in my head>

Ryan: He saw some of my free YouTube videos and totally supports.

Me: He totally supports because that’s bringing business to him, since you work for him. You need to (1) check your employment contract for language around side gigs or competition and (2) talk to your boss about your plans.

Ryan: Ok yeah yeah thanks for the advice but I’m pretty sure I’ve got this.

<six months later, in which time Ryan did not talk to his boss but did announce the launch of his company>

Ryan: My boss is pissed.

Predictably so. I’ve seen this same pattern happen so many times, <insert joke about nickels and retirement>.

Margaret (fake name) got this same advice from me and said “It’s totally cool, our previous CEO knew about my side business and even encouraged me to do it.”

My dear Margaret, did you say “our previous CEO”? As in the one who is no longer your boss?

That’s like telling the cop who pulled you over for speeding that the last cop just let you go free.

Margaret did not talk to her new boss.

Margaret blasted her new business all over social media.

Margaret got fired.

Don’t be like Margaret.

Talk to your boss.

Say something like “I wanted to let you know about my plans to start a side business. I don’t anticipate that it’ll have any impact on my performance here. But I’ll be announcing it soon on social media and I don’t want that to take you by surprise.”

Be prepared with information about what your contract says regarding side work. Especially so if your side gig is similar to the work you perform in your day job.

You may have to speak to details of your plans, like your anticipated clientele, in order to illustrate how you aren’t creating a competing business.

But you don’t want to overindulge.

It’s a tricky conversation, for sure.

I’m not trying to fool you into thinking this conversation is going to be easy or clean.

It could get uncomfortable.

It could lead to putting some agreements in writing or, sorry about this, even more meetings.

Even if you follow my guidance here, there are no guarantees.

I *had* talked to my boss. I had my boss’s approval to work side gigs in writing. Girl, I had receipts!

And it still didn’t matter to HR, who told me I had two weeks to close my side business.

Their rationale: The topic I wanted to develop on the side – data visualization – could potentially become something the company wants to focus on also, at some point in the future, if they so decided one day. So, my side gig was considered competitive.

Hypothetically.

But, listen, bottom line is HR doesn’t care whether their logic is cohesive or fair. It doesn’t matter what your boss put into writing.

So why should you talk to your boss, if the conversation amounts to protection as fragile as an eggshell?

Because you’ll feel like you did it right. You’ll have gone about the process with your ethics and integrity intact, no matter the outcome.

On the other hand, don’t talk to your boss.

If you know your employer explicitly bans side gigs of any kind or you just have a boss that’s a little unhinged, don’t tell them about your plans.

You’ll be fired faster than you can tweet that you’re open for business.

Instead:

1. Build up the infrastructure of your business while you’re still employed.

2. Hoard your salary in a savings account.

3. Then quit your day job and launch your new website in the same day.

How to Fire a Difficult Client

The first time I had to fire a difficult client, my pits sweated right through my shirt as I was composing, backspacing, and rewording that email.

Look, we’re gonna to do our best to make sure we don’t ever end up in this position, but sometimes you have to fire a difficult client.

I encourage you to do this at the second sign of inappropriate behavior. For the most part, I’ll give people grace on their first asshole comment, late payment, or questionable Zoom background.

But the second time?

Cut your losses and get out.

You don’t necessarily even need to have a clear egregious error. Sometimes you just drift apart. You’ve got a 5 year contract and 2 years in you’ve decided you want to shift your business focus.

Instead of providing a full suite of graphic design services, you’re pivoting into the niche of writing each wedding guest’s name in calligraphy on individual grains of rice that they’ll chuck at the happy couple. Totally cool.

Pivots happen all the time.

The bottom line is don’t do this:

Even if you really really really want to.

When you recognize it’s time to part ways your first stop is your contract. Whip that baby out.

It’s gonna have a section on cancellation. The most common clause I see says that the contract can be cancelled by either party with 30 days’ notice.

Ok, cool.

Email your client and say… whatever you want. But not too much. Unless you want to.

Crystal clear?

My point is you aren’t obligated to say much but if you’ve had a good relationship and want to preserve it, you can provide some detail.

How to fire a difficult client:

You can be as efficient as “Hey there – It breaks my heart to do this but I need to sever our partnership. Our contract asks for 30 days’ notice – please consider this the notice. I’ll continue to give my best on this project in that time and I have someone in mind I’d like to transition you to if you want a recommendation.”

You don’t have to mention calligraphy on wedding rice.

You also don’t need to provide a recommendation if your client is a jerk. Because the colleague you’re recommending doesn’t deserve that behavior either.

If they’ve specifically breached the contract in some way, you don’t have to wait the 30 days either. You just need to point to that clause in the contract, like “Todd, when you commented on the size of my butt at last week’s meeting, it was a breach of the sexual harassment clause of the contract, which is cause for immediate cancellation. I’ll be sending my final invoice over shortly.”

I’ve been in less clear situations where I had to say something like “The ongoing reshuffling of my scope and responsibilities is making it impossible for me to fulfill the obligations laid out in our contract. Further, I need to be able to trust a partnership – that’s how we plan out our business strategy. This partnership is not working for our business model any more.”

Copy/paste these as much as you need.

Take a deep breath and hit send.

And if you’ve loved these folks, consider shipping them a parting gift of wedding rice.

Do not forget to send the final invoice.

Sometimes we don’t review our contracts very carefully before signing and end up agreeing to a clause that’s less fair, like one that says only your client is allowed to cancel. If that’s you, still try one of these options listed above. Chances are that once you convey that you’re unhappy, they’ll also want to part ways.

If you’re screening your prospective clients well, firing a difficult client will be rare (so bookmark this page for when you need it). I have to do it once every other year.

When it happens to you, it sucks but I’m here for ya. Email me and tell me what happened and how they reacted. We’ll get through it together.

When to Disappoint Others

Here’s a story about first time I got a gig through LinkedIn.

Jennifer worked at a ~~ prestige beauty company ~~ and needed a consultant to revamp the 100-slide PowerPoint about the state of the prestige beauty industry for their upcoming conference.

I said yes, even though (1) the deadline was tiiiiiight, (2) I don’t really love doing this kind of design work, and (3) I don’t know jack about the prestige beauty industry.

The pay was structured as a flat dollar amount per completed slide.

Jennifer sent me the deck from last year that “just needed to be updated” (famous last words).

Each slide had at least 100 different elements on it – dozens of textboxes in 4 point font, photos arrays of expensive neck creams. I very quickly saw that the reasonable dollar amount per slide was going to equate to far under minimum wage, with all the work it would take to redesign even a single slide.

I spent a whole weekend in my office, cranking out remakes according to what I knew to be best practices for slide design.

Sent it off to Jennifer Sunday night.

She freakin hated it.

Her email was something like “this is not prestige, this is not elegant, this is not beautiful.”

That hit me like a gut punch.

I took another shot at it, still without any real idea of what prestige, elegant, and beautiful would look like to Jennifer.

I’m sure I fell short. I sent off the next draft, which, at this point, was like the day before the conference. I never heard from Jennifer again, despite my follow up emails.

I had disappointed her.

The right time to disappoint her would have been back when she slid into my LinkedIn DMs. I should have said no. The project wasn’t a good fit. The answer should have been simple.

Or, I could have asked for a sample slide so I could get a sense of the scope of the work. I woulda opened the sample slide, laughed out loud in my office, then politely declined the job – disappointing her.

What do those two opportunities have in common?

They come before the contract is signed.

The best time to disappoint someone is before you sign official paperwork.

We risk damaging our reputation and wasting everyone’s time and energy when we don’t engage in a thorough discovery phase before we ink signatures.

In order to honestly engage in a discovery phase, you’ve gotta know what work you will and won’t do. What lights you up and what’ll be a slog. Who you love to work for and who you don’t need to support.

Those distinctions are blurry at best when we’re desperate for work or flattered by the ask.

You need clarity about your focus and purpose to enter into a discovery phase. (You also need a list of client red flags to look for.)

Most of us skirt this. Because we want to “remain open to new opportunities.”

But clarity about your focus and purpose brings you strength and confidence.

You might think, what’s the harm? You only lost one weekend of your life saying yes to Jennifer.

Not so, my friend. I lost my time, my energy, and I risked my reputation. And as an entrepreneur, time, energy, and reputation are all you’ve got.

So now I know better. I asked for a sample to get a sense of the scope. It’s part of my discovery process.

Let’s trade stories. How did you disappoint a client, after the contract was signed? And what changes have you made to your discovery phase as a result? Shoot me an email.

Being Strung Along

The thing about being strung along by a “potential client” is that you often don’t know it til it’s too late. Let’s look at what happened to a couple of my students and let their hindsight become your foresight.

No work without a contract.

Sometimes we make it easy to string us along. Like when we agree to work we wouldn’t normally do, for the promise of a future contract.

One of my previous mentees (let’s call her Trudy) accidentally set herself up for being strung along. She realllllllllly wanted to partner with this organization. It woulda been a big fish to add to her portfolio.

In her early conversations with her point of contact at this org, they seemed super eager to work together. So much so, that the client asked Trudy if she’d be willing to jump in on some small tasks (warning sign #1) at a low (warning sign #2) hourly rate (warning sign #3).

Trudy didn’t know me then, so she said yes. The client said it would just be temporary while they write up the bigger contract and get it in place.

Did Trudy ever advance beyond low wage task labor?

No my friend she did not.

And she was too embarrassed about the scope of her work there to ever include this client in her portfolio.

The client doesn’t know what they want.

Another student of mine (code name: Blanche) got stuck in a months-long string-along with a potential client because of “decision by committee.”

Similar to having too many cooks in the kitchen, decision by committee is an excellent way of slowing progress to a casual stroll through I Don’t Know What Do You Think Land. Have you and your partner ever entered into starvation because neither of you could decide what you wanted to eat for dinner? Like that. But with ten partners.

Blanche had a typical initial meeting with this client to lay out the possible solutions she could offer to the problems they were experiencing. They seemed to have come to agreement about the way forward. Blanche went home and waited for a contract.

And waited.

Blanche checked in but by this point, the finer details of the conversation had been lost, so the potential client asked Blanche to write up the plan in a proposal (note to Future Blanche: Write and send the proposal immediately after the initial meeting.)

Blanche sent the proposal and waited.

And waited.

When she checked in again, the potential client said the team needed to really think about whether the proposed solution would solve the right problem. Could Blanche meet with the whole team and help them talk through their problems?

I’m gonna skip to the end of Blanche’s tale: Blanche dealt with so much waffling you’d think she could open an IHOP franchise. This client liked the idea of working with Blanche (or, at least, of having a consultant) but couldn’t ever make a decision about where to start.

I actually suspect they didn’t have the funds to invest in the right solutions but didn’t want to say that to Blanche’s face, so they just let it playyyyyyy out.

Look, some clients really do take months of nurture before the project comes to fruition and you get that sweet contract in your hands. You’ve gotta relationship build. They’ve gotta convince some team members to swipe right on you. Procurement processes and vendor onboarding – the creepy evil twins staring at you blankly at the end of the hallway of consulting life – can take a long, long time.

You’ve gotta learn how to tell the difference between when they really do need time and when they’re stringing you along. Here’s how I tell:

Check-ins should advance the plot.

If you’re not hearing a reply after you send a check-in email, wait a week and send another. We all have those weeks from hell where we can barely breathe. But if you don’t hear anything after the second check-in, move on with your life.

When you do get a reply, it should include some decision or action or next step with a date attached to it.

Like “My team and I have a meeting to discuss this project next Tuesday and I’ll get back to you then.”

or “I have a few more questions. Can we schedule a Zoom to discuss?”

These are check-ins that advance the plot.

If your check-in gets a reply like “Thank you for checking in!” or “We’re still thinking about it.” you’re being strung along and it’s time to walk on by.